QSC’s Own Motion part 2: how staff quality and practice leadership impact resident safety

February 7, 2023

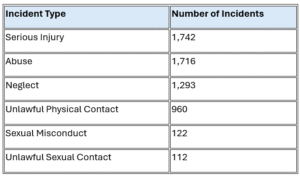

If you missed our most recent article, the Own Motion Inquiry conducted by the NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commission (QSC) into Supported Independent Living (SIL) has revealed some alarming insights. With the 7 selected providers accounting for a significant portion of the SIL cohort, the findings from the Own Motion Inquiry cannot be ignored.

In part 1, we reviewed the root causes of harm in SIL, took a closer look at violence between residents, and questioned the effectiveness of Behaviour Support Plans (BSPs) and controls versus the ultimate underlying problem: insufficient funding.

As part 2 of the series, this article delves into the drivers of staff-generated abuse, evaluates the chances of implementing meaningful change, and outlines three ways providers can respond to the Own Motion Inquiry.

Violence originating from staff

The QSC has stated that it will take steps to eliminate psychological abuse in SIL homes by launching a targeted campaign. They believe that by following the NDIS Workforce Capability Framework, they can select a workforce that is less likely to engage in abusive behaviours.

Meanwhile, the QSC acknowledge that it is generally a minority of staff who perpetrate abuse against people living in SIL homes, they also rightly identify that new and agency staff may lack the information and training necessary to correctly meet the needs of people with disability.

Unfortunately, even though the NDIS suggests that utilising the “recruitment framework” will help address the issue of bad apples, we are here to demonstrate that the effective size of this intervention will be marginal at best.

Selecting with zero error is impossible

Accurate selection is a serious problem across all sectors. The point of a selection process is to accurately predict applicants’ behaviours. Therefore, the construction of valid selection tools, known as psychometrics, requires that our instruments are reliable and encapsulate and predict important behaviours – we call this validity.

It is important to consider that all the staff who harmed clients in this sample must have passed an iteration of the screening check, which means that additional background checks are unlikely to improve safety.

Instead, the QSC has proposed the NDIS recruitment framework as a solution to psychological abuse in the scheme. While the framework is undoubtedly comprehensive, it lacks robust psychometric founding or evidence. Unfortunately, a robust meta-analysis of recruitment processes suggests that the best we can hope for is an R2 of .63, with little incremental value on aptitude tests.

The fact is aptitude worsens most predictive in cognitively demanding settings. While support work requires these skills, it is much more dependent on traits like integrity, compassion, empathy, and conscientiousness, which are notoriously difficult to assess in employment settings.

Undoubtedly, improving selection processes will enhance safety for people with disability. However, they deserve a selection process that is evidence-based and grounded in the science of selection. The QSC may find great value in creating a valid and effective assessment tool or psychometric method to reduce the risk of abuse.

Devising robust psychometrics is hard, and due to the infrequent reporting of psychological abuse, it may be challenging to establish the predictive validity of the assessment if only a limited number of abusive individuals are identified.

To jump on the AI bandwagon, a tool such as ChatGPT is a possible solution to this problem. However, due to sample sizes, it may select traits beyond our imagination. Until that day, organisations must consider supervision as a primary safety measure.

Redefining SIL supports: the role of effective practice leadership

This brings us to the viewpoint of Professor Christine Bigby, which we believe offers a feasible solution: frontline practice leadership. The challenge is, “if we can’t choose staff effectively, how can we guarantee competent supervisors?” This issue is exacerbated by the financial limitations of the cost model.

The NDIS cost model assumes that most supervisors are level 1. It is worth mentioning that the recent version of the cost model does not include a clear distinction of the supervisory levels, but the cost has not changed significantly, indicating that the original assumptions likely still apply.

The 2020-21 cost model assumes that a supervisor would receive pay at SCHADS level 3.2 and manage 15 Full-Time Equivalents (FTEs). What does practice leadership entail in this context?

SCHADS Award quick facts:

The SCHADS Award definition of 15 FTE translates to 570 hours per week. This means a supervisor’s team will have an average of five staff working at the same time. With the inclusion of casual contracts, the average supervisor is responsible for managing a team of 20-25 staff.

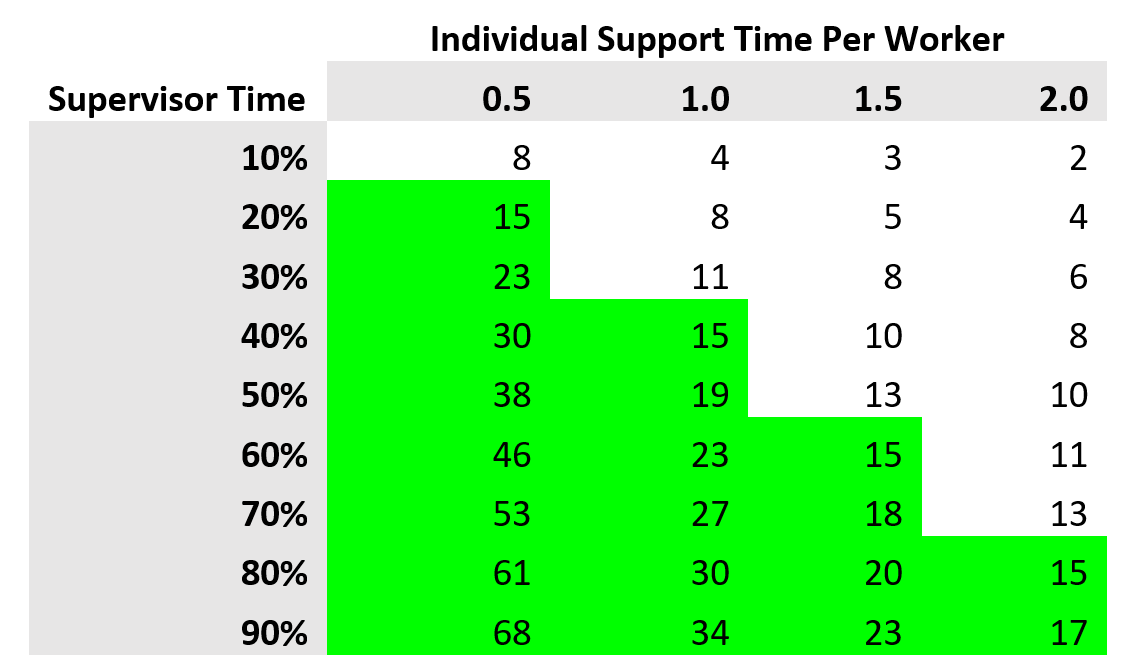

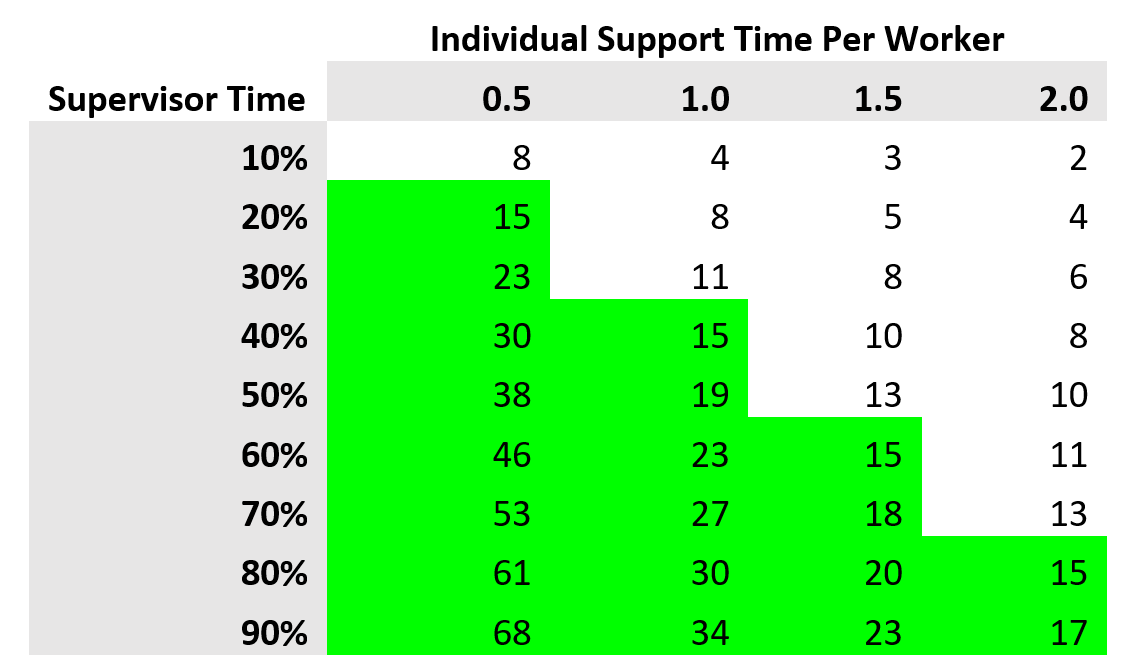

Below is a table showing the number of staff who can be supported based on the weekly support hours provided per worker and the percentage of the supervisor’s time required to deliver frontline practice leadership.

For example: A supervisor dedicating 50% of their time to practice leadership, with one hour expected per worker could adequately supervise a team of 19 people. The catch is, we’re not aware of any supervisors with 50% capacity at this time.

In this case, practice leadership is stable when providing one hour a week and using approximately 70% of the supervisor’s time (assuming 100% productivity).

In some cases, group homes with multiple staff members may be able to reduce the leadership requirement. Experienced staff may also require less leadership or less frequent leadership. However, given the high turnover rate in the sector, it is possible that new teams may be spread across several suburbs, reporting to a single supervisor. This raises a crucial concern for the NDIS: how to fund practice leadership in a situation where the leadership requirements are highly variable.

The above table also highlights a peculiar aspect of the NDIS, where perspectives on its implications vary greatly. Some parents and carers believe that one hour of direct support per staff member per week is inadequate, while others view supervision as of minor significance. Views on supervision are one of the few areas where differences among organisations exist, in fact, a parent asking for “warranties” on the level and frequency of practice leadership may be one of the few ways that they can guarantee quality in group homes.

Unfortunately, one hour of supervision per week alone cannot prevent staff-generated abuse, but it can serve as a deterrent and improve the workplace culture, so abuse is not tolerated. However, using the current recruitment framework is unlikely to eliminate staff-generated abuse, as these tools do not meet basic psychometric standards.

What can I do as a provider?

The following three steps can improve your organisations’ response to the Own Motion Inquiry and provide a better service while being prepared for future audits:

- Implementing practice leadership with key metrics to prevent abuse and meet future regulations.

- Embedding robust whistleblowing and probationary assessments to help identify inappropriate staff after they are hired.

- Developing and monitoring comprehensive placement matching practices to evaluate co-resident violence. Where the risk is high, consider forming a panel to mediate different perspectives of operational leaders until the agency takes responsibility for funding decisions.

At Empathia Group, we are confident that changes to SIL regulations will take the form of practice leadership and recruitment optimisation at minimum. It seems unlikely that the NDIS will offer supplementary SIL funding for these additional requirements.

Organisations that move quickly and make practice leadership the centrepiece of the quality of their product and find a way to signal this to the market may be able to seize this change as an opportunity.

Additionally, we expect the most successful organisations will commit to practice leadership by measuring the volume and quality of their leadership via 360-degree feedback, engagement surveys and raw time-in-placement data. This data can provide competitive reassurances to customers in the notoriously opaque SIL market.

If you are a SIL provider navigating what the Own Motion findings mean for your business, we would love to hear your perspective. Reach out to our team.

Subscribe to Empathia Insider to ensure you don’t miss part 3 of our deep dive into the QSC’s Own Motion Inquiry.

Share this article:

Continue reading Empathia Insights

Kafkaesque: The Moral Hazard at the Heart of SIL

Kafkaesque: The Moral Hazard at the Heart of SIL Dean Bowman November 18, 2025 Supported Independent Living The Federal Court's...