- Want to get in touch?

Dean Bowman

November 18, 2025

The Federal Court’s $2 million penalty against Lifestyle Solutions is a stark document. It details 18 incidents of violence over two years at a single group home in Woongarrah, NSW. For providers, it reads like a cautionary tale. But for those who look closer, it reveals something more troubling: a blueprint of a system where financial incentives and duty of care exist in direct conflict.

This is the Kafkaesque reality of Supported Independent Living. Providers are held legally accountable for participant safety, yet critical levers that determine that safety are controlled by other parties. The result is a profound moral hazard, where the risks of systemic failure are borne by providers and participants, whilst the savings are accrued elsewhere.

A System That Could Not Learn

The court orders against Lifestyle Solutions, finalised on 14 November 2025, show a system that did not learn from its own data. Between October 2019 and October 2021, Hakone House recorded repeated incidents of physical aggression between residents. The same incidents triggered multiple, compounding breaches of the NDIS Practice Standards:

The 13 May 2020 incident involving physical aggression by one resident (AT) towards another (Ms Leicester) was found to constitute a failure across all four standards simultaneously. The provider’s systems were failing to do more than react. Data from November 2019 did not change the outcome in May 2020, nor in the many incidents that followed through to October 2021.

The individual penalties for each incident ranged from $30,000 to $166,500, with the total reaching $2 million. For context, a typical SIL house generating a 3% margin on $1.2 million in annual funding creates a $36,000 surplus. This penalty would consume the combined annual surplus of over 55 such houses.

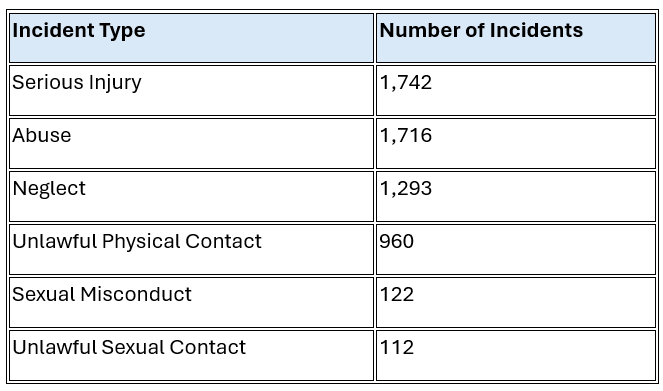

To view the Hakone House case as an anomaly is to misunderstand the sector. The NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commission’s own Own Motion Inquiry into SIL examined 6,269 reportable incidents across 1,075 SIL sites, representing 18% of the total SIL cohort. The findings are confronting.

Residents in SIL are, on average, five times more likely to be sexually assaulted than the national average. The data shows that inter-resident violence is a prevalent and embedded risk:

The situation at Hakone House represents the extreme end of a risk spectrum that many providers navigate daily. Staff and co-residents represent the most significant vectors of harm to those residing in SIL. Critically, harm inflicted by another person with disability in a SIL setting is a direct reflection of the support they are receiving. This analysis is not about placing blame on individuals with disability, but rather evaluating whether they are receiving adequate support.

This is where the situation becomes Kafkaesque. The system is structured in a way that creates a predictable and severe moral hazard.

The Supervisory Constraint

The NDIS cost model funds supervision based on a span of control of one supervisor to 15 full-time equivalent (FTE) staff. The assumption, as articulated in sector analysis, is that “the cost model pays a supervisor at SCHADS 3.2, assuming a 15 FTE span of control.”

In a strict 1:3 SIL setting, this translates to real operational constraints:

Each 1:3 house often involves participants with complex support needs: seizure management, mealtime protocols, community participation, nuanced social interactions. Even in the best circumstances, a supervisor’s time is stretched thin.

When you scale that ratio up to 1:6 or higher, the same single supervisor could be responsible for double the participant load, meaning substantially more support plans, staff coordination, and incident follow-ups. The cost model does not increase supervisory resourcing to reflect this increased administrative or clinical oversight. More participants multiply the demands on the same finite supervisory bandwidth.

Constrained Escalation Pathway

The second element of the moral hazard is more subtle but equally significant. When a participant is placed in a SIL setting, their funding determines the ratios of support. If that participant has been misassessed or if their needs escalate after placement, there is no simple or safe mechanism to provide them with the supports they actually require.

The current system lacks a robust, rapid escalation pathway to the NDIA. When a provider identifies that a participant’s funded supports are inadequate for their presenting needs, the options are limited and slow. The provider can either absorb the cost of unfunded supports to maintain safety (eroding already thin margins) or continue with funded supports whilst waiting for a plan review, risking both participant wellbeing and the compliance breaches evident in cases like Hakone House.

This is where the moral hazard becomes particularly acute. The provider bears the immediate financial and legal consequences of the funding-need mismatch, whilst the systemic response mechanisms are controlled elsewhere.

Why It Cannot Be Simple

The absence of a rapid escalation pathway is not without reason. Such a mechanism would be open to serious abuse by providers seeking to maximise revenue. A system where providers could readily trigger funding increases would create perverse incentives that undermine the integrity of participant planning.

For an effective escalation mechanism to exist, the NDIA would need to invest substantially in on-the-ground analysis and intervention capacity. This would require skilled assessors able to distinguish between genuine support need escalation and provider-driven revenue optimisation. The cost and complexity of such a system is significant.

Further, if major plan revisions become routine mid-cycle, the current fee-for-service funding model may prove inadequate. Block funding arrangements, or alternative funding mechanisms that remove the direct financial incentive from escalation requests, may be necessary. These structural changes would represent a fundamental shift in how SIL is funded.

This is the NDIA’s side of the problem: how to create responsive planning without creating moral hazard in the opposite direction. The current system attempts to solve this through careful upfront assessment and fixed funding periods. But when assessments prove inadequate, or when needs genuinely escalate, participants are left in the gap between plan cycles, and providers are left managing risks they cannot fully control.

The Data Blindness Problem

This moral hazard is compounded by a lack of operational visibility. When a house shows a 73% wage-to-revenue ratio in financial reporting, that single number reveals almost nothing about the underlying causes. The problem could be a genuine funding shortfall that requires advocacy for a plan review. It could be systematic overservicing. It could be roster inefficiencies. It could be unfunded support gaps that are creating safety risks.

Without granular data that distinguishes between these scenarios, providers are making critical decisions in the dark. Resources get allocated based on incomplete information. The result is often reactive: cutting where cuts seem possible, rather than addressing root causes.

Where the Cuts Actually Fall

Sensitivity analysis conducted on the sector shows that once corporate overhead is reduced to an ultra-lean level (the cost model benchmarks overhead at the 25th percentile of providers), any additional budget shortfall comes at the cost of frontline support. When vacancies and surplus hours exceed 12%, providers lose enough operating margin that the only remaining flexibility is in the discretionary elements of service delivery.

Without operational insight to identify where genuine efficiencies exist, providers under financial pressure make blunt cuts. Supervision and training, being less immediately visible to participants and families, become targets. This is precisely backwards. The research on practice leadership in disability services, particularly the works of Beadle-Brown, Bigby, and Mansell, demonstrates that high-quality support depends on in-situ coaching: engaged observation, responsive guidance, and proactive safety measures.

When financial strain hits, supervisors become the system’s shock absorber:

The Lifestyle Solutions case, with its repeated failures to learn from incidents, bears the hallmarks of a system where supervisory capacity was overwhelmed. But without data showing exactly where the financial pressure was originating, the cuts likely came from the wrong places.

The Question That Cannot Be Asked

There is an unspoken tension in the sector that the Hakone House case forces into the open. The NDIA’s planning process often funds supports based on an individual’s needs in isolation, with insufficient consideration for the dynamic risks of a shared living environment.

When a resident’s behaviours escalate unpredictably, the provider is left with a Behaviour Support Plan (BSP) that may be theoretically sound but is practically impossible to execute without creating unfunded support hours. The implicit question becomes: what is the acceptable level of risk of violence for the NDIA when determining a person’s support needs?

The BSP Fallacy

The system places considerable faith in BSPs as the mechanism for managing complex behaviours. Yet strong evidence suggests that the vast majority of BSPs are not high quality. Recent psychometric reviews have highlighted a lack of predictive validity measures in BSP assessment tools. A 2024 Dutch study found limited effect sizes even for implemented plans.

The Kafkaesque trap here is threefold:

The Hakone House case and the Own Motion Inquiry suggest that the current funding and planning model implicitly tolerates a level of inter-resident harm that would be considered unacceptable in any other community setting. Despite the potential efficacy of well-designed and well-implemented BSPs, the reality is that some instances of violence between people with disability cannot be effectively managed through these plans alone when the resourcing does not match the complexity.

Why are people with disability subjected to violence in their own homes whilst the NDIS gathers data on an individual “in vivo” or whilst a BSP “takes effect”? This question reveals the dehumanising nature of the current arrangements.

The Non-Negotiable Duty

Before exploring how providers might navigate this Kafkaesque system, it is essential to state clearly: providers take on serious obligations when they open a SIL home. Regardless of the prevailing systemic circumstances, the safety of participants is the first priority of any organisation. These obligations surmount any appeal to efficiency or monetary gain.

The systemic pressures described in this analysis do not diminish provider accountability. They explain why the current arrangements make safe, sustainable service provision extraordinarily difficult, but they do not excuse failures to meet the fundamental duty of care. When a provider accepts NDIS registration and opens a group home, they accept full responsibility for participant safety, regardless of funding adequacy, supervisory constraints, or escalation pathway deficiencies.

The Federal Court made this abundantly clear in its findings against Lifestyle Solutions. The penalty was justified precisely because the provider failed to meet its obligations to participants, and no systemic excuse was accepted.

The Problems That Must Be Solved

Given the non-negotiable duty of care and the Kafkaesque structural constraints, what problems must providers solve to meet their obligations?

Problem One: Operational Visibility

The most fundamental problem is that many providers do not know, with precision, what is actually being delivered on the ground. When a board asks the executive team whether participants are receiving all the hours stated in their service agreements (derived from the Roster of Care), can the answer be given with confidence?

Direct reconciliation between payroll data, timesheet records, and the documented Roster of Care is technically possible, but uncommon. This creates a tremendous risk in the context of the Lifestyle Solutions findings. If the court found that a provider failed to deliver committed supports, how certain can any provider be that they are not experiencing latent underservicing?

The sector may be carrying unknown compliance risk simply through a lack of visibility. Without daily reconciliation between what was planned and what was actually delivered, deviations become systematic before they are detected.

Problem Two: Resource Allocation Without Data

When financial pressure requires difficult decisions, providers need to understand where genuine efficiencies exist versus where cuts would compromise safety. The 73% wage-to-revenue ratio discussed earlier is meaningless without understanding its components.

Is the budget strain caused by a funding shortfall that requires advocacy to the NDIA? Is it caused by roster inefficiencies that could be resolved without impacting participants? Is it caused by unplanned support needs that require immediate escalation? Without this clarity, providers risk cutting supervision and training (which maintain safety) when the actual issue is elsewhere.

The problem to be solved is creating visibility into the true drivers of financial strain, so that decisions are based on evidence rather than guesswork.

Problem Three: Learning From Incidents

The Lifestyle Solutions case demonstrates a provider that could not learn from its own data. An incident in November 2019 did not prevent a similar incident in May 2020, which did not prevent further incidents through to October 2021.

The problem is creating a system where incident data automatically informs future risk assessment and operational planning. When an incident occurs, what changes in staffing, supervision, or support ratios? How is that change documented, implemented, and verified? Without a closed-loop system, providers are reactive rather than proactive.

This is particularly critical given the BSP quality issues discussed earlier. If the BSP alone is insufficient, and if supervision is the demonstrated effective intervention, then providers need systems that ensure supervisory capacity is protected and that incident patterns are visible before they become systematic.

Problem Four: Evidence for Escalation

When a provider identifies that a participant’s needs have escalated beyond their funding, the current escalation pathway to the NDIA is slow and requires substantial evidence. Providers need to be able to demonstrate, with concrete data, that the funding-need mismatch is genuine and significant.

This requires showing exactly what supports are being delivered, what additional supports are required, and what the financial impact has been. Without this evidence base, escalation requests lack credibility, and participants remain in the gap between their funded supports and their actual needs.

The problem to be solved is creating the audit trail that enables evidence-based advocacy, whilst also ensuring that the provider is not inadvertently creating the case for their own non-compliance through documented underservicing.

The Imperative for Change

The financial mathematics are unforgiving. The $2 million penalty against Lifestyle Solutions would wipe out the annual surplus of over 55 typical SIL houses. For providers operating on 0-5% margins, a single serious compliance failure represents an existential threat.

The Kafkaesque nature of SIL is that providers are accountable for outcomes they lack the full power to control. The NDIA controls funding levels, effectively determines participant groupings through its planning decisions, and sets supervisory ratios through the cost model. Providers control operational execution and bear legal accountability.

This asymmetry cannot be an excuse. Providers who open SIL homes accept full responsibility for participant safety. But the asymmetry does explain why operational intelligence is no longer optional. Without systems that provide visibility into what is actually being delivered, that identify where financial strain is originating, and that create evidence trails for both compliance and advocacy, providers are navigating blind.

The sector-wide data is now clear. Inter-resident violence is pervasive, not exceptional. BSPs are often inadequate. Supervisory capacity is stretched beyond effective limits. These are not isolated failures but structural features of the current arrangements.

The question is whether providers will invest in the operational capabilities needed to navigate this reality before they become the next case study in regulatory failure. The problems identified here have known solutions. The technology exists to reconcile delivered care against commitments, to identify genuine funding shortfalls versus operational inefficiencies, and to create learning systems that prevent repeated incidents.

The Lifestyle Solutions penalty is not just a cautionary tale for one provider. It is a signal to the entire sector that the margin for operational blindness has closed. Participant safety is non-negotiable, and the systems required to ensure it are now fundamental to sustainable operation.

This analysis is based on public Federal Court orders (NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commissioner v Lifestyle Solutions Pty Ltd [2025]), the NDIS Commission’s Own Motion Inquiry Report into Supported Independent Living, and published sector-wide research. It is intended for informational purposes and does not constitute legal advice.

For more information on comprehensive roster optimisation and service delivery monitoring solutions, visit empathiagroup.com.au/ndis-sil-suite/

Join an exclusive community of providers receiving our eNewsletter Empathia Insider. Get first access to NDIS business insights, free provider resources, and special offers direct to your inbox.

Empathia Group is a collective of business consultants focused on creating sustainable, long-term success for NDIS service providers.

Appointments outside of standard business hours available by request

Empathia Group Pty Ltd © 2022. All rights reserved.

5rotfk

gn5n6j